Walking for God

Aham Brahmasmi. If Gauri keeps repeating I am Brahman, maybe the stickiness of the early afternoon will evaporate entirely like last night’s conversation between her and Mo about her perennial self-sabotaging behaviour. Mo knows how to dig up her flaws and dangle them in front of her. Talented Yogi.

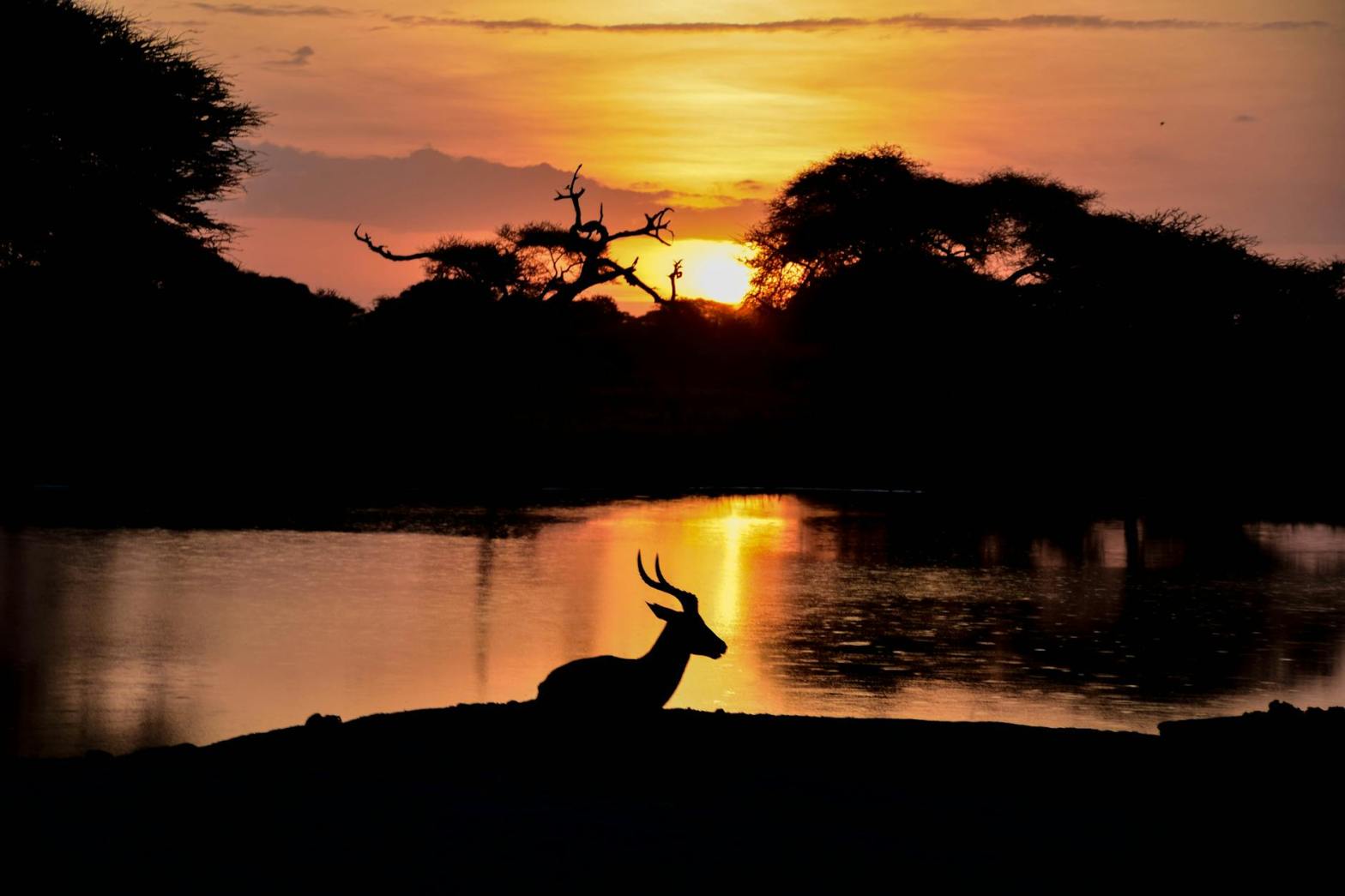

“If you remember you’re the vastness of consciousness,” Mo said just after the first half of their epic wander along the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia, moonlight glinting on the ocean like underwater flashlights, “and not the thoughts in your head, not even your emotions or anything you can observe, then you’ll stop hurting yourself. You won’t need to ban yourself from good things. You won’t have designed flawed presentation slides at work on purpose, you won’t tell the people who love you to leave you because you’re cursed, you won’t let others take what’s yours to enjoy.”

Gauri didn’t say a word. She threw shells into the sea and watched the water jump. They’d opened the single packet of coconut buns they received from their latest round of begging. The buns stuck to each other like co-dependent friends. Mo tore the first bun off the second and handed it to her. She wasn’t hungry even though they hadn’t eaten in a day. That was the practice, Mo said before they set off from Kuala Lumpur for their month-long wandering trip, we beg for everything, food, transport, a place to stay, it’s the route to God.

“And listen,” his voice suddenly soft and kind, “we’re walking for thirty days to shed our ignorance, our false self. You can’t reach the light if you’re holding on to the rubbish. Stop going against yourself, Gauri.”

She bit into the spongy bun, gifted to them by a tailor from Punjab who volunteered at the Sikh temple where they had their last meal of chappatis and thick, salty dhal. The tailor was poor, she lived in a tiny, musty room decorated with abandoned cobwebs and mysterious dark markings on its four chipped walls, but she insisted on buying them a packet of coconut buns from the sundry shop opposite the temple, next to her humble room. “You’re walking for God,” the woman whispered, reverence in her voice, “I have to help you. It’s my duty.” The tailor couldn’t believe people still did things like this, wandering through the wilderness of the world with nothing but a single cloth bag and trust. “This is like a story from the holy books,” she continued, “you know those wise men who gave up everything and travelled naked through forests and villages, wanting nothing, needing nothing. Cruel people threw stones at them, but there were also good people who gave them food and shelter. I have nobody here in Malaysia. My family is in India. I have very little but to give you both some food is what brings riches to my small life. You must sleep here for one night. Take my bed, I will sleep on the floor.” Gauri immediately felt guilty. She had no right to be parading as a holy woman. In her pre-wandering life, she had accidentally poisoned a cat, she’d actively practised lying, she got high on Ganja, she cursed at her parents in private, and she mainly didn’t wish people well because people mainly didn’t wish her well. She openly wept in front of the tailor and the next morning, she found a beautiful white cotton bag beside her, surreptitiously sewn by the tailor while they were sleeping.

Gauri scrunched up the bag to her nose. It smelled of poverty and kindness. She wanted to cry. She had no right to be here, enjoying the tailor’s hard work, her gift of buns. In front, the sea was gorgeous and it looked as though stars were dropping from the sky. What did she do to deserve this type of beauty? This type of generosity?

“Embrace your life, Gauri,” Mo said, as though he’d entered her mind, “Your problem is that you don’t value your existence. So, you throw it around, give it away to whatever and whomever is there to take it. And there are always cannibals waiting to gobble up what they can to make them feel a false sense of power.”

“Tell me what to do.” She swallowed the bread, thinking about the poor tailor and what the woman had done for them. More stars fell from the sky, lighting up the ocean with silver fire. Tears rolled down Gauri’s cheeks.

“This is your problem, Gauri. You haven’t blessed yourself. The whole universe can bless you but if you don’t bless yourself, nothing will ever happen. Nothing.”

The conversation stuck to her like antique bubble gum. It didn’t leave her alone all night, all morning, and now, on the second leg of their wandering journey, she can’t shake the damn thing off. But what should she do? She can repeat Aham Brahmasmi over and over again but for what? She doesn’t feel like the vast ocean of consciousness Mo and the scriptures say she is. What she really is, she wants to say but is too afraid to admit because she’s meant to be transcending it all, is this rigid, frigid woman who doesn’t know what she should do to atone for every shitty thing she’d done in her life.

Meanwhile, Mo is peaceful. He’s sauntering up ahead, immersed in Brahman. Is that called a walking Samadhi? Lucky bastard. Being a Yogi has nothing to do with it, he claimed, he was just good at forgetting. Mo, the prodigious Yogi she met by accident at a bus stop three years ago. He was sitting cross-legged on the ground, chanting loudly: Om Asato Ma Sadgamaya Tamaso Maa Jyotir Gamaya Mrytyor Maa Amritam Gamaya Om Shanti Shanti Shanti. She was at that point in her life when her aloneness was no longer cute or funny, it was dangerous and sad; she’d left home, fought with every friend, curated her own firing from the job of her dreams, had exactly twenty-five ringgit in her bank account, one loaf of semi-green bread and half a packet of processed cheese in her rented room which also, she discovered the night before, had developed an ant-infestation problem. She was ready to swallow Mo’s chants. He didn’t particularly want her, he confessed later, but he pitied her and decided to help her transform out of her wretchedness.

Which is why they’re here on this east coast beach, to jump over the world. They’re here to throw themselves into Enlightenment.

She has to fight for this because he had to fight for this for her.

The late morning sun singes her head. They’ve walked over ten kilometres, mostly on coarse-sand beach, pristine and empty apart from thousands of silent hermit crabs. She stopped to stare at them two kilometres ago, Mo marching in front of her, oblivious to her revelatory communion with the scrambling crustaceans. Light bounced off their pearly shells, shocked her into a moment of paralysed bliss. Her tongue remained stuck in its cage. She wanted to scream, “what beauty!” like a silly foreign tourist but she didn’t because she couldn’t. It wouldn’t have mattered anyway. There was nobody around to hear her. Best part was she didn’t care if anyone witnessed her. Didn’t need others to make her feel good. No money in her bag, the last coconut bun consumed two beaches ago—they agreed to travel for a month on faith and surrender—she’d never felt this happy.

But inside her is the feeling she’s had most of her life: none of this will last, don’t get too comfortable.

Her feet squish into soft, sinking sand. Even after ten kilometres, each time her feet go in, she imagines them never coming out. It feels like quicksand, she complained to Mo and he told her to conquer her mind. Titiksha, he reminded, you have to develop better titiksha, otherwise your mind will always be shaky. Transcend your febrility, Gauri. Then he returned to silence.

This is their twelfth day roaming streets and beaches without money, without pre-determined accommodation. And still she doesn’t know what he means by self-blessing. Go off on your own, Gauri, give yourself permission, Mo had said while they waited by the road for free transport. What does it mean to give herself permission, permission for what?

“Mo!”

She shouldn’t be calling out to him, she knows, especially since he sealed them both off in silence, to heighten their practice. They’re here not without intention, he often reminded her. They’re not here to sunbathe, not to have a holiday. They’re here to fulfil the highest goal of human civilisation. It’s what the Buddha did three thousand years ago, and Shankaracharya, and the Rishis of the Vedas.

“Mo!” she insists.

He’s racing ahead. She quickens her step, to keep up. She has to clarify what he means by self-permission, self-blessing.

“Mo!”

“Mo!”

“It’s important, Mo! It’s about the practice!”

But with each shout, he skips and runs. She should stop now, let him be, but she’s afraid. Why is he doing this to her? What kind of punishment is this?

“Mo!”

She can barely see him now. He’s sprinting off the beach. She keeps running. He’s not looking back. Had he always been this way?

“Stay detached,” he once told her, “that’s the way to inner strength.”

Is detachment cruel? Is it cold? Dismissive?

This must be it. He’s detaching himself from her, throwing her off a cliff and asking her to find her own way out of the inevitable. Mo, but wait, I want to tell you I am finding it hard, my head spins badly and I’m not ready to be alone or to be Brahman, I just need a bit of time, I can’t do this, I don’t even know what I’m supposed to do, oh my god, oh my god, please wait.

But Mo has vanished.

She wants to ask him how she’s meant to bless herself, the whole concept of self-blessing is foreign to her, this whole beach and planet and human life is foreign to her, she’s never been shown the way, what is the way, oh my god, oh my god, I am not holy, I am not worthy of the hermit crabs, of the poor tailor’s gifts. She slows down. Her entire body burns in the midday heat. Her feet ache from the run. She tries to neutralise her panting but nothing happens. Her breath is going out of control. Focus on the in-breath, the out-breath, that’s what Mo taught her, but there is too much chaos in her breath for that to work. She collapses on the sand. She clutches the white cotton bag the tailor sewed for her while she slept. She hugs it tightly and feels a burst of warm air in her chest. She keeps the bag in her arms, sobs into it liberally, indulgently, and stays there, roasting in the noon heat.

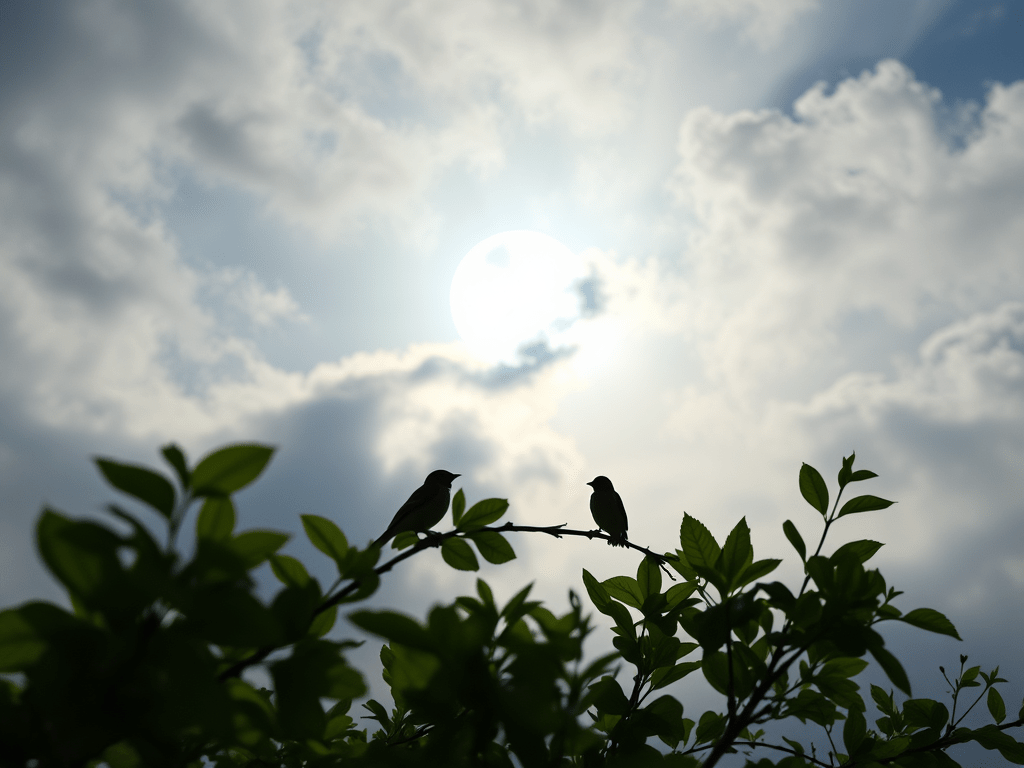

She opens her eyes. The sky twists and turns. Birds squawk shrilly. The world swirls in lurid white light. It feels like the ending of something, like the long-awaited arrival of death.

Gauri sits up, scoops sand into her hands, squeezes hard and hurls the damp clump at the water. It lands just at the edge of the shore. She stares at the gentle waves and screams, “Mo, Mo, you bastard, Mo, I know what I will do now. Get out, get out, I don’t care! Be as evil as you want. It’s your contract with God, not mine. I have my own plans, Mo, Mo, you bastard Mo.”

It will take her a day and a half, at least, to walk back to the tailor’s home. She knows how to beg for food and water along the way, Mo taught her that. Gauri has no plans for what she will do once she arrives at the tailor’s home. Perhaps thank the woman, embrace her, confess her sins, make the tailor a cup of tea, whatever. It doesn’t matter. Gauri isn’t worried. She’ll figure it out the moment she lands at the place she experienced the first real glimpse of God in her life.

Shivani Sivagurunathan is a Malaysian author. Her first novel, Yalpanam, was published by Penguin Southeast Asia in September 2021.

Her poetry collection, Being Born (Maya Press) and her book What Has Happened to Harry Pillai?: Two Novellas (Clarity Publishing) came out in 2022.