Mary Magdalen Seated Before a Mirror

After Georges de La Tour, Penitent Magdalen, 1640

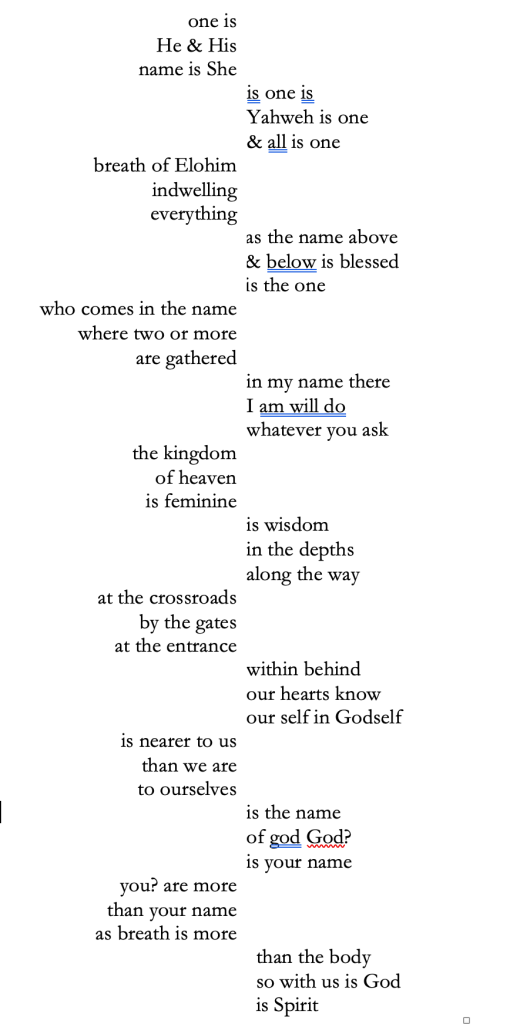

1.

Beneath the wood

ran lines of water,

cutting across the root.

The wood had rotted;

it broke off in her hand,

splintery like a clod of earth,

crawling, and beneath her hand

the sharp running blades –

her dry, soundless weeping,

her solitude.

2.

She knew that she had fallen:

the cold descent

a jewel of knowledge

placed upon her.

Close by was the little dresser

with its oval glass, oblique,

discreet in dust –

unwilling to embarrass her.

The dresser in a child’s size;

she had to fold herself up to be near it,

to trace with her finger the oval,

the old view. The first.

She placed her fingers on the surface:

here; here.

She bent forward, turned her head

to the sliding impossible image,

the eyelash, the whole, the furnished room:

now it is there.

3.

To her flesh was laid the edge of the knife,

division of eternity.

The skin was lifted away.

Veils fluttered,

unresisting the edge that caught, lifted,

found easily the quick fraying,

the edge everywhere at once,

the separation at first schematic

along the warp and the weft,

then from each point

equal motion in all directions was possible,

all outwards,

the veil lifted: torn, adrift, smoke.

The muscles of the body lay exposed,

bound in curving sheaves,

braided into one another at the narrow end;

the sheaves of the reed boat journeying,

at every point at the crossing

of descending lunar spears,

and the horizontal breaking

of silver multitudes

of blades cutting the water.

Braided around the globe of the eye,

the cavity of the mouth,

locked fingers of the open hand,

down the neck, across the shoulders,

the breast, the belly, the arms

and the thighs and the lower legs,

all the limbs and parts,

locked fingers drawn tight,

then loosening,

rising to curve,

then drawn, twisted tight,

drawn down.

What word, what step,

what composed and thoughtful gesture

was possible,

drawn from the locked knot of fingers

blind, groping to open and close,

unclenched, mute?

And the slashed triangle,

slashed like the backbone of a fish,

slashed like the locked, interwoven edges

of the sheaf?

4.

To the veil, the reed boat, the sheaf,

from the mirror, the water, the wood,

a candle approached,

as flame, and light.

Cynthia Sowers was a Senior Lecturer at the Residential College of the University of Michigan. Until her retirement in 2019, she developed and taught interdisciplinary courses for the Arts and Ideas in the Humanities Program. Her past teaching and current creative activity are centered on the engagement of literature and the visual arts. She has published poetry, drawings and paintings in The Solum Journal (2020; 2021) and poetry in Amethyst Review (2021). She has published a short story, “A Trap to Catch the Earth,” in The Carolina Quarterly (Spring/Summer 2021).