The Baby

She watched the baby floating on the raft in the long pool frantic with children. He was not a baby, but he was the baby, and his white white legs and arms kicked and paddled. His brothers and sisters kicked and leapt and shouted around him and she could watch them and love them without thinking about them. Now the baby went away from her, and now he came back, and if she let herself look too closely at him or think too closely about him, she would be grateful, as she had been so often before, for the black sunglasses that caught the light shearing from the sky and arcing off the pool to flash inscrutable signals across the blue water and toward the brown bay.

“Lovey,” her husband said.

By slow degrees the glasses turned to give him back himself. She saw him see himself and watched as if from his eyes as he held to her the bourbon coke fizzing with chipped ice. She took it and sipped, eyes closed, feeling the cold breath of it flow up under the glasses across her eyelids. Then she let the glass rest on her belly, and the cold chilled a ring around her navel though the black one-piece, and she opened her eyes again and watched the baby kick and snort and smile in the sunlight.

“Hey, Dilly,” her husband said to the baby, “Watch how you flex them muscles. Might have to beat the girls off with a pool noodle.”

“Come on, Daddy!”

She closed her eyes again and felt her fingers tighten on the cold curve of the glass. She had watched the girls skirt the pool, glancing, whispering behind hands, smiling or stricken or disturbed, and she had seen the boys at the deep end, leaping high in the water that streamed from their perfect selves, peering at this strange thing paddling in the shallow end, some new fish or turtle, surely not a boy like them. And their laughter rang out, and she thought of the porpoises they had seen that morning from the balcony, sporting in the dawn, and she tried to see the porpoises again and to listen to the silence of the morning as the boys laughed.

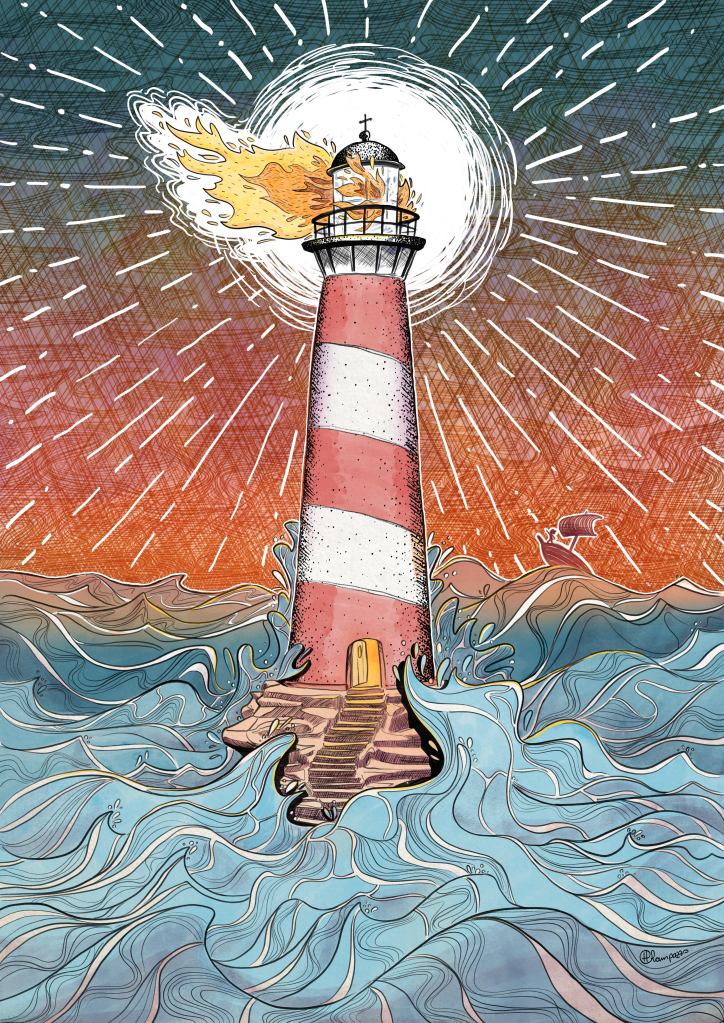

As the baby spoke, the wind rose up and ruffed the surface of the pool and blew him away. She rose, pressing the drink with her left hand to her belly, reaching out with her right, stifling a cry as he paddled back toward her, smiling, lifting a hand to wave. She waved back, and reclined again, listening to the wind as it rattled the palms. The sound of terror. Of her own soul rattling, whipping, tearing in the wind no longer in gusts but in the long relentless scream of the hurricane when they’d come here as they always had to weather storms, thinking surely this was safer than their home in New Orleans, city below sea level, city like a bowl waiting to be pressed beneath the dirty dish water and fill up.

And the wind had risen off the bay then, like a band tuning up, with horn blast and strum and tickling and then, as if leaping like a world from instinct nothingness, the anti-musical blast of it, a single howling note in a thousand voices bending up or down returning always to the same shriek. She’d watched it dandling the palms, feeling already disaster’s advance as the wind whipped out the fronds and the waves curdled as behind her in the room the children watched television and laughed and screamed while with the glass door of the balcony an inch from shut she watched the wind advance to what she’d known it would become.

And Dev had been inside, watching her watching the storm spread out until there was no more of the world for it to swallow, as if it had always been there and only now come visible. At last the children, too, had fallen silent at the unabating roar. She turned and saw them gathered at the glass, her vision of them shrouded by the dark hair the wind whipped up from behind her to veil her face. And the palms had rattled and torn. Then the rain had poured in its torrent, dimpling the shaken sea, and she came inside trembling. Dev had handed her a towel, wrapped her in it when she did not take it herself. And Tully, the littlest besides the baby, had said how he wanted to go home, he wanted to go home, he wanted to go home, and Dev had told him no, they would wait right there and watch and have you ever seen such a sight as this can you believe it just imagine being out in this, and they had watched from their second floor windows until the power failed and darkness fell and they had piled into beds and lightly, tossing, drifted into dreams.

The baby was a baby then, and she had nursed him in the dark and stepped among the sprawled out sleepers and spoken softly into his ear how sweet and good and lovely he was. It was true. He was sweet and good and lovely and all the more lovely because he was what they called in the Dark Ages a monster. His eyes, too big, leaked and rolled in a misshapen face, like stone abandoned by the sculptor, and on his hands and his feet he had only four digits, and each was like a tiny thumb. She wept for him and loved him and pressed him to herself and knew that he would always be the baby because, however she loved him, she would not face whatever might open her womb again.hi

Dev slept in the dark and she heard him there, nearest the glass, whistling faintly through the nose as he slept. And she whispered to the baby, who curled against her in silence, twisting his head to one side and then the other.

At last she felt the baby was asleep and laid him down in the little crib and lay beside her husband. She thought she would not sleep, yet as her eyelids drifted shut for the thousandth time, they seemed to spring open to a world all changed. Then Dev was gripping her shoulder softly, whispering gently but with urgency, “Lovey. Lovey. We better go out in the hall, it’s getting bad out there, I mean bad bad.” The wind shrieked, and there sounded great thuds like the booming of leathery wings. She thought of her mother in the city and then of the banana plants at her own bedroom window and then she was not thinking but simply rising, doing as she must.

The children woke and stretched in the bleary night and asked what was it and where were they going and what was wrong and they chattered their excitement and huddled, all, in the hallway and subsided into silence as the hotel shook, holding them invisible and silent in the heart of it suspended between the two distant windows at either end of the long darkness. Looking to the grey besotted trembling panes she felt that all was wrong, all wrong, and worse than for the hurricane that seemed about to wash them from the earth when from the roar as if from beneath a blanket came a sound.

“The baby!” she said. “Dev, the baby, get the baby.” She had torn at the door but he said, “No, Lovey, let me, let me, he’s alright, I got him,” and turned the handle and vanished as for a moment the baby’s cries rose. The door shut. Distantly there came a sound as of a wine glass falling from a startled hand to shatter in bloody constellations across a kitchen floor. It came again, again, the sound, irregularly, sometimes louder, then softer. Then within their room it came again as the sliding glass exploded in the wind and the baby’s shrieks soared into hysteria. And Dev returned, the door flying open as if in fright, and as he slammed it behind him the wind took it and smashed the fingers of his right hand. He screamed, and she took the baby, and the older girls managed to shut the door as Dev’s screams continued and curdled the baby’s to madness.

There was blood on the baby’s head and she tasted it as she kissed him and spoke to him and pressed him close, folding herself around him against the storm, against his father’s cries dying to silence beneath the outer roar which was itself already settling. When finally she slid to the floor and let the baby rest on her thighs it was like freeing an animal or a spirit trapped for ages in a tree. And he had slept, they all had slept, save her. After all they were safe.

Dev’s hand had healed, and his face where the glass had shattered against him, though his cheeks wore the thin scars like scratches in a fish’s scales, and the hand that offered her the drink she cradled to her belly now beside the pool was knobbed and crooked with its healed-over brokenness and she thought again how like a saint he was with light breaking through the crazes and cracks of his suffering and she was unmoved by the thought, whether to envy or fervor, but she was grateful for him and glad, for his sake, for his goodness, and something whispered this was love.

She hadn’t wanted to return, not to this particular curl of Gulf Coast, but the children had asked and asked and Dev had smiled at them and let his eyes slide over to her, saying nothing, never imploring, never in the dark discussing what he, they, wanted. And one evening she had said, very softly, as if watching someone else say it, “We ought to go to the Bay this weekend.”

And she sipped and watched the baby drift and paddle. As he turned on the raft she watched the pale netting of scars whiten in the light, and she thought of the surgeries to come, the endless line they’d said could, could, give him something like a human face. She stopped herself thinking, gave herself instead to seeing him instead of not-him, holding him against no background but the life that was theirs, glistening in the sun. She sipped, and the sweetness was the sweetness of all the rest, and the wind rose and rattled in the palms.

Beneath the rush and clatter of the wind she heard another sound advancing. Opening her eyes she saw a row of boys’ heads bobbing in a line, bobbing nearer, rising like the human heads of seals and declining again into the clear blue of the pool. They were pointing and chuckling and glancing as they bobbed nearer, nearer to the baby, pointing and chuckling and looking to ask what was this, what was this fish or turtle or boy.

Watching them, she felt herself watched. The baby was smiling at her, squinting and smiling, misshapen image of herself, of Dev, of her own father. The boys came nearer, and still the baby smiled, and she rose, clutching her drink and lifting a hand as if to stop them coming nearer.

The baby turned, looked at them, and said, in a loud, laughing voice, “Y’all got a problem?” And he rolled, smiling, onto his back on the float, and the sun flashed as the water ran off the pale belly in its webbing of scars and she saw him for an instant illuminated, terribly himself.

The boys did not laugh. They looked at each other and drifted away, and when their laughter rose again it came from their own pure sporting in the sunlight. Dev took her hand, and she looked at him. He smiled, and she closed her eyes again and did not let go.

Daniel Fitzpatrick is the author of two novels, two poetry collections, and a translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy. He is the editor of Joie de Vivre: a Journal of Art, Culture, and Letters for South Louisiana, a member of the Creative Assembly at the New Orleans Museum of Art, and a teacher at Jesuit High School in New Orleans, where he lives with his wife and four children.