Memos To the Great Attractor

#7

Touchstone

Here I go again, picking up pebbles for my pocket

until I become too heavy to swim. Nostalgia.

What was a comfort, maybe still is,

turns cumbrance, possibly lethal;

but finally, just comes down to mementos of skin, of bone,

down to composing notions, the face in the glass.

Time to box some more china for Angel's Treasures

at the village church, to pitch out more old traces,

the irrelevance now of genealogies. Broken-limbed trees.

I’ve pared down the piece of precious found wood to a nub

that might yet become a pencil or be fitted with a blade

like the ones the architect fingers for models and designs,

nub round as the crown a mother shoves through into its separate possibility.

You know about all this, lover and schemer. Building up and taking down.

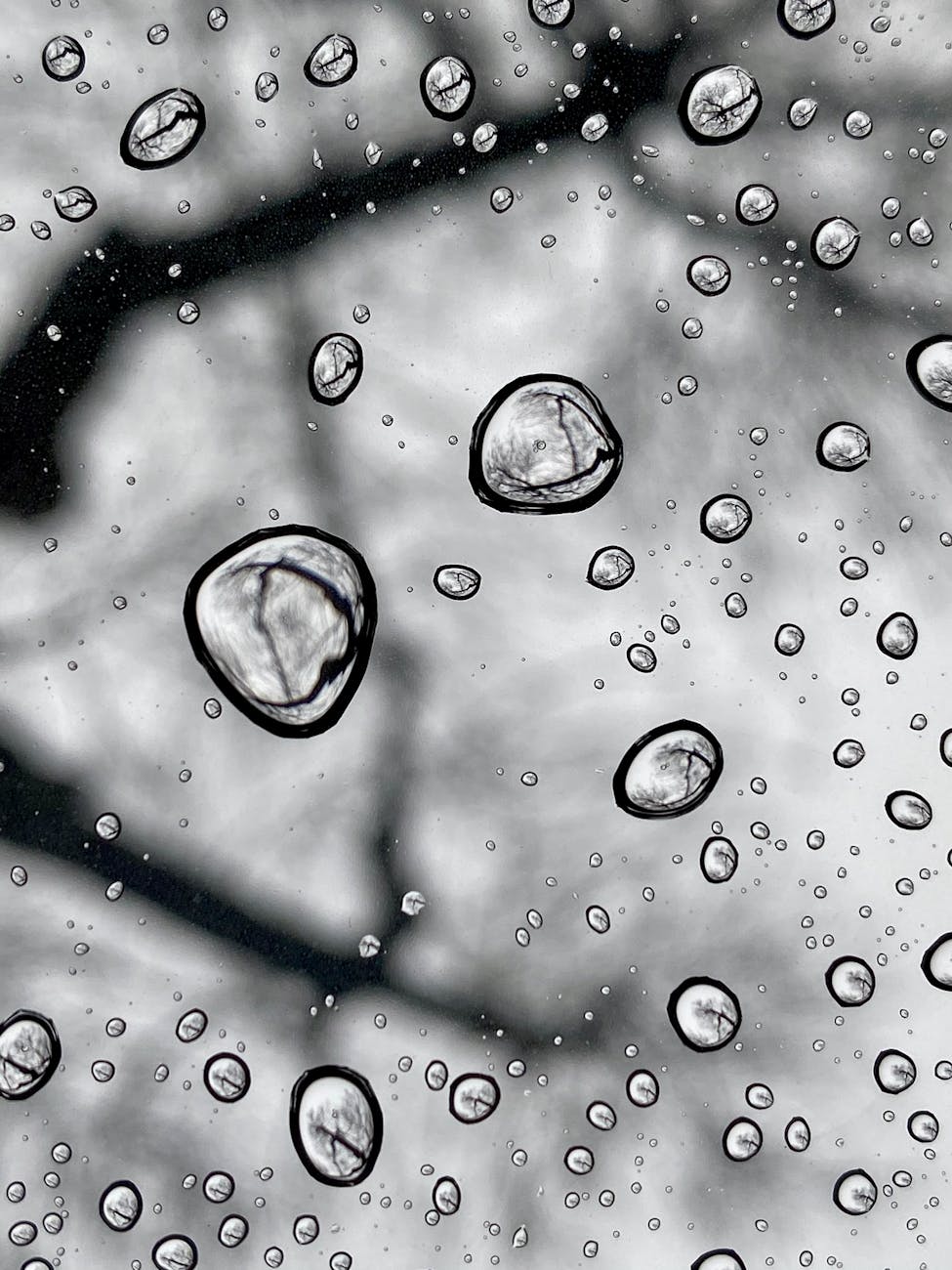

This touch-stone in my palm's jasperite like the Makapansgat Cobble

the collector Eitzman found in a South African cave, seeing in it a face

that seemed to be carved — by an ancient Australiopithican,

so he thought — cradled nubbly in his palm like the touch of the ancient hand

of a sculptor reaching out to him. But no.

A natural simulacrum, experts said, made by pressure and heat

and the pummeling of ages. Nothing more. But then they noticed

it lay nine miles from any geologic source,

so it was carried by a prehistoric collector into that cave

of human remains, someone who saw that same face

looking back, another explorer seeking connection

from a deeper antiquity, a sacred emblem

left behind, to carry on speaking the holy

into a future loneliness, a shared wonder.

A much-published bi-national immigrant, gardener, Bonsai-grower, painter, Jennifer M Phillips has lived in five states, two countries, and now, with gratitude, in Wampanoag ancestral land on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Phillips’ chapbooks: Sitting Safe In the Theatre of Electricity (iblurb.com, 2020) and A Song of Ascents (Orchard Street Press, 2022). Phillips has two poems nominated for this year’s Pushcart Prize. and is a finalist in the current Eyelands Book Competition, and Cutthroat’s Joy Harjo Poetry contest.