Thinking of St Aebbe at a Bernat Klein design workshop

‘The designer should be a visionary and a dreamer.’ Bernat Klein, Design Matters

Klein’s old ways harmonise with nature

a seasonal blend of hues, in planes of colour

We discern through visual inspiration,

sea thrift, feather from St Abb’s Head.

The prayer is in the noticing:

think of the color purple.

What can we learn from lilies and birds?

Watch as day's eyes open to the sun,

birds sing, preen, feed.

Rhythms both seen and heard.

Design shows care for individuals

affirm Klein, the Aesthetic

and Fibonacci Principles.

With lush Briar, Holly, Maple, Mace

tweeds of slub twined with ribbon of velvet,

beauty confers dignity. Perhaps also truth?

Sustainable wool, bamboo,

hemp, linen, mohair. Nuns chant

'The earth is the Lord's

and everything in her.'

Resilience builds through daily rhythm,

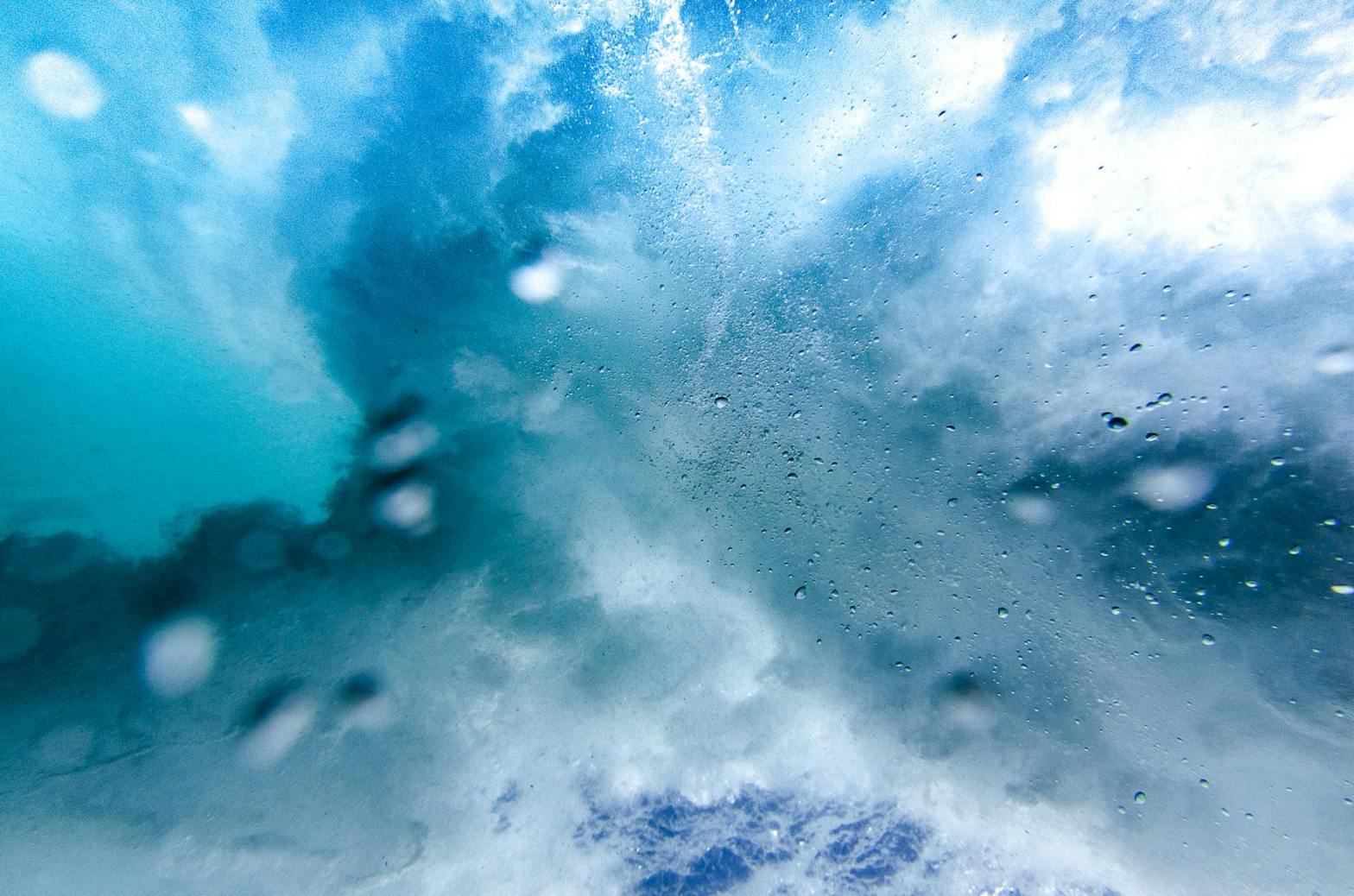

pink thrift thrives in salt sea spray,

and very dry summer conditions.

Prayer work play. Prayer work play.

In warps and wefts of everyday

repetition is the Designer’s friend

pink thrift, gull from St Abb's Head

dark green, grey-cream, sage, cerise

dark green, grey-cream, sage, cerise

Prayer work play. Repeat, repeat.

With care to leave blank margins

find a natural line, play

and work with what feels right

Cut upwards, disrupt, cut through the pattern repeat,

experiment. Tape end to end, reconfigure

now blank space is ripe to create in.

Magma rises, makes new crust at plate margins,

as in the silence of negative space

old stories weave new connections.

Sublimation makes for strong imprints.

Inspired while teaching Christian attitudes to animals and the environment in Religious Studies, Barbara Usher now cares for retired ewes who bring their lambs at foot, and ex-commercial hens on her 8 acre animal sanctuary, Noah’s Arcs. Her poetry has been published in Borderlands: an Anthology, Amethyst Review, Dreich, Green Ink Poetry, Last Leaves, Last Stanza, Liennekjournal, and in the Amethyst Press anthology Thin Places & Sacred Spaces. Her work appeared on the Resilience soundscape 2022 for Live Borders, with background accompaniment of her late pigs. She writes on Celtic saints, farmed animals, and her local area.