Worship of Light

On a high plateau far away,

lived a race of people who enslaved light.

No Zoroastrians, these, for they had usurped the sun:

Their technology encompassed fluorescence,

lasers, mirrors, globes and gigantic lens.

Originally harmless in their faith,

they worshipped bio-luminescence, keeping fish and worms

in temple tanks where devotees would rub and click

on rosaries of beaded quartz for mystic sparks.

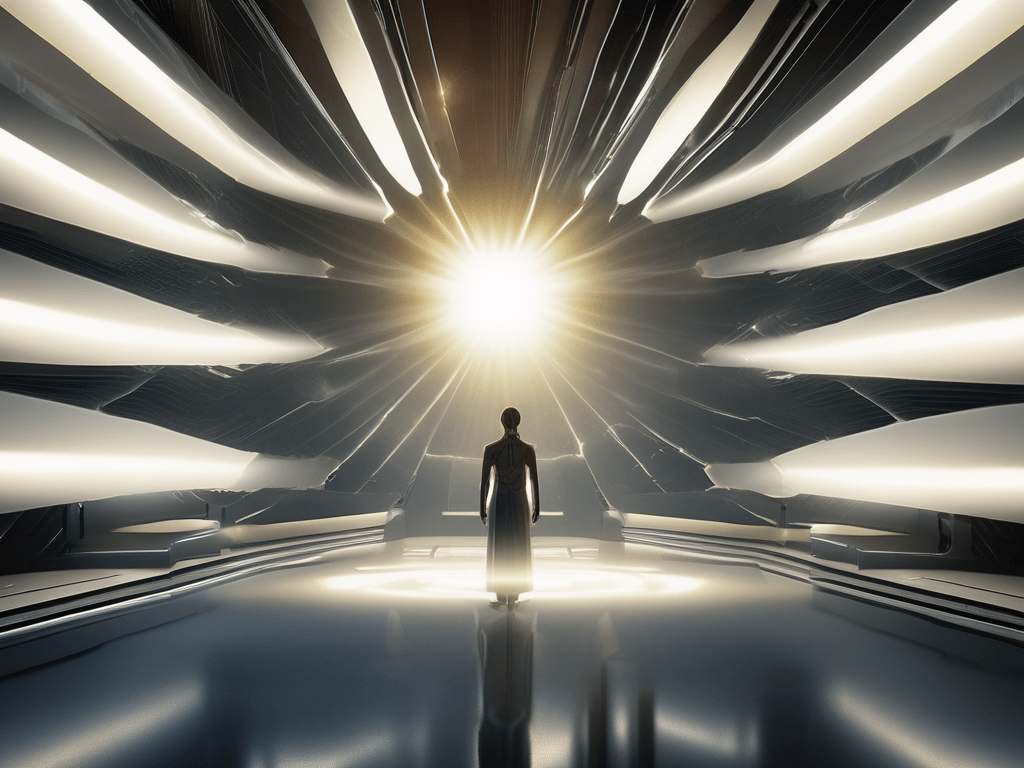

But priests were now advanced to inner rings

of atoms and their photons—pressuring

with heat and forced velocity,

splitting the very finest grains of paradise.

They persecuted unbelievers—named them heretics—

who lived in cellars now and bunkers underground,

for world had gone insane with zealots and religious wars,

as wayward balls of fire ripped through ether.

And they all went blind in that realm of captured light,

for their god, in emergence from dark ruptured elements,

revealed just a fraction of his bright transcendent glow,

exploded to engorged illumination

like the stars of Van Gogh...

Clive Donovan is the author of two poetry collections, The Taste of Glass [Cinnamon Press 2021] and Wound Up With Love [Lapwing 2022] and is published in a wide variety of magazines including Acumen, Agenda, Amethyst Review, Crannog, Popshot, Prole and Stand. He lives in Totnes, Devon, UK. He was a Pushcart and Forward Prize nominee for 2022’s best individual poems.