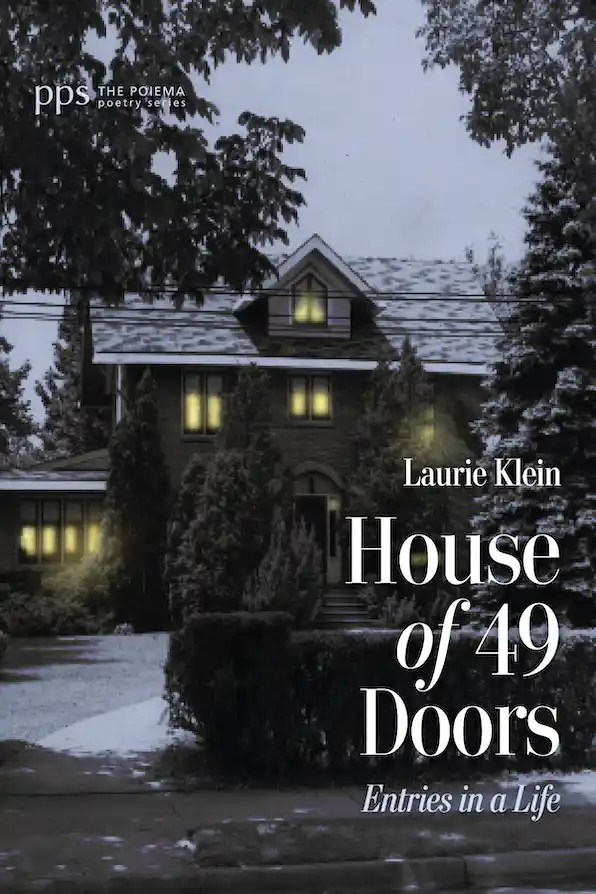

House of 49 Doors: Entries in a Life by Laurie Klein, 114 pp, Poiema Poetry Series, Cascade Books, 2024

If you frequented church in the last decades of the 20th century you may well have sung “I Love You, Lord”. The song was a worship staple through my own childhood, and as I grew into adult faith I internalized its words as a kind of prayer. In the personal introduction to her website, Laurie Klein notes that she wrote the song “weary and bone-lonely…while our first child slept” (“About Laurie Klein, Scribe”, lauriekleinscribe.com). Now, decades later, Klein is a contemplative poet, and a remarkable one at that. In 2015 her first book of poetry, Where the Sky Opens: A Partial Cosmography, was published in D.S. Martin’s Poiema Poetry Series. In March, this series published her powerful second work of poetry, House of 49 Doors.

Appearing nearly ten years after her first collection, House has evidently grown from the kind of deep soul work that characterizes Klein. In email communication with me, Klein noted that her recent work has often emerged from “praying and writing in the wee hours”, when her writing was able to “bypass distractions and…insecurities” to “shak[e] loose imagery and candor”. It also sees something of a return to the childlike simplicity of “I Love You, Lord” after the more somber, adult reflections of Where the Sky Opens, no doubt because the work takes Klein back to childhood memories, moving between two perspectives, “Larkin”, her child self, and the mature “Eldergirl”, a polyphonic device that merges maturity and simplicity with pathos and delight.

This interplay of childlike faith with “hard-won” wisdom is ever-present when speaking with Klein. Though returning to her childhood, Klein has chosen a period of her life that, while containing much sweetness, also reveals “festering pain”. “Letting two voices process,” Klein observed in our recent correspondence, “helped me squarely face feelings long-buried”. The child brought with her a “quirky innocence” that disarmed the adult, while “Eldergirl” could convey “the hard-won lessons and gifts of hindsight”, “pointing toward the patient, redemptive interventions of God, over time”.

Joy in Klein’s work is indeed hard-won. Both her books take as their focus gritty and painful subjects, while delicately unveiling grace with them. For Klein, poetry is especially adept at this, capturing the “beautifully incalculable” alongside the “dismaying”. Indeed, pain first brought Klein to poetry, with her father’s death in 1996. “Stratified grief and numbing stage 4 depression steamrolled me,” she explained. Haunted by “images from [her] past”, she turned to poetry for help and has not left it. “Writing is my favorite way to debrief, arm-wrestle doubts, clothe my fears so that I can see their shape, shake out the wrinkles, expose the stains.”

Poetry also dovetails with contemplative practice. “The year my dad died,” Klein wrote, “I signed up to learn a medieval calligraphy font. I hoped a focused return to the ABCs, stroke by stroke, might reanimate my curiosity, coax me beyond depression”, the formation of her letters gradually “feeling akin to prayer. An alphabet of presence.”

From calligraphy she moved towards creating a Book of Hours, and from there to “other early church disciplines, like Lectio Divina” and centering prayer. Like returning to the ABCs, this practice of prayer reflects a desire to recover the basics of faith and living, like learning to breathe aright.

Out of this rich spirituality emerges a delightfully earthy, grounded mysticism. Klein’s poetry captures, as her first book’s title suggests, both the cosmic and the intimate, though she is characteristically self-deprecating when I asked how she achieves this balance: “Oh my. Not there. Not yet.” Of that book’s subtitle, “A Partial Cosmography”, she says, “I did so want to be taken seriously.” Yet it does not strike me as pretense. The idea of a “partial cosmography” suggests the ways that we see only, as St Paul puts it, “in part”, “as in a mirror” (1 Corinthians 13:12): we cannot possibly take in the whole of the cosmos and all it signifies. Yet the “sky opens” in small places where we can imperfectly see God at work in all things.

And Klein’s eyes are constantly being opened, sometimes through pain. The central story behind her first book is the “radical faith shift” that her husband experienced “after three decades of shared worship ministry”. “The outcome of this,” she says, “upended many areas of our lives.” This “upending” is captured in the remarkable and deeply moving “Dreamer and Bean” poems woven throughout the collection, capturing moments where our experience teeters on the edge of our faith’s comprehension, while hinting at how it reconfigures on the other side.

A similar urge to reconfigure was the starting point for House: “Amid the relentless brokenness of today’s world, I was itching to resurrect the almost magical house I grew up in,” wanting, she says, “to hear from creatures…who once kept me company,” to “re-glimpse a firefly’s wink inside a rolled leaf”, indeed, “to chase delight.”

Delight is evident on almost every page of House, albeit tinged with grief. Emerging through the book is the story of her beloved “uncle Dunkel”, returned from the Korean War with PTSD, ultimately taking his own life. Klein’s child self is urged by her father to never speak of how her uncle’s body was found. Significantly, it was never Klein’s “plan to address the hushed-up death”. “But Kid Larkin had other ideas.” Praise God for Larkin’s instincts. Klein could very easily have chosen to remain in the “magical house” without opening treacherous doors; or she could have let grief cast darkness over all its illuminated moments. She does neither. Fireflies sparkle while adored uncles die; and in the book’s postscript, beloved grandchildren can stand with us as we revisit the past’s agony and beauty.

Though Klein has “weathered” almost five decades since “I Love You, Lord”, its simple faith is never far away. “The song’s final line—surely, my life’s greatest request—haunts me…It challenges me to continually receive, then express, the God-given sweetness of Love amid days that are fractious, heartwrenching, sullied and worn.”

Klein’s poetry is the fruit of this daily prayer, echoing the sweetness of God found in the long-haul. House of 49 Doors sparkles with unexpected grace.

Unattributed quotes are from personal email correspondence between Laurie Klein and Matthew Pullar.

Matthew Pullar is a poet and teacher based in Melbourne, Australia. In 2013, he received the Young Australian Christian Writer of the Year Award for his unpublished manuscript Imperceptible Arms: A Memoir in Poems. He has published three books of poetry, including The Swelling Year: Poems for Holy and Ordinary Days, and has had poetry published in Soul Tread, Proost Poets and Poems for Ephesians.